Indonesia’s disaster agency, BNPB, has indicated that it is expecting El Nino to severely impact Indonesia with an extended dry season. The primary concern of the disaster agency is the drought and its potential impact on the lives and livelihoods of people across the archipelago.

Specifically, the agency has undertaken measures for extra crop planting in the event that crop failures impact local communities. It is also encouraging people to use water saving measures as the dry season continues, and undertaking cloud seeding programs in some areas.

The agency has also indicated that there will also be a heightened fire risk this year, specifically for Jambi, Riau, South Sumatera, West Kalimantan, South Kalimantan and Central Kalimantan.

BNPB has provided more than 1600 pieces of additional fire fighting equipment in Central Kalimantan alone to assist with fire prevention and suppression.

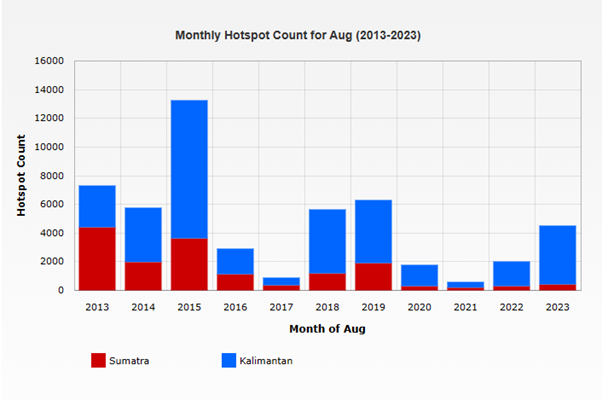

Although there have been some dire warnings, particularly from international campaign groups, about the potential severity of this year’s fire season, the monthly hotspot count for August hit around 4,500 for Indonesia. This compares with around 6,700 for 2019 and 13,600 for 2015 – which were the most recent peaks for fires across Indonesia.

Source: http://asmc.asean.org/asmc-haze-hotspot-monthly-new#Hotspot

That said, Indonesia’s agencies expect the full effects of the dry season to peak through September and October.

For the palm oil industry, it means that extra resources will need to be mobilised in terms of preventing and suppressing fires as they occur. Despite what Western campaign groups argue, fires are incredibly destructive for the industry and its communities, resulting in considerable economic, social and environmental losses.

This has been lost on many news outlets reporting on fires in Indonesia in the past, as well as internationally. The Guardian, for example, recently blamed Hawaii’s devastating fires on the development of plantation agriculture over the 150 years. The real question posed – but not addressed – by this article was how the new owners of the abandoned plantations allowed those plantations to be overrun by invasive grasses that paved the way for the fires. It’s very likely that if those plantations were still operating with good agricultural practices, greater care for fire prevention would be undertaken. That is the case in Indonesia; it’s well understood that large operators do not start fires, and put considerable resources into fighting fires started by smallholders using fire for clearing. However, this is rarely covered by international media chasing only headlines and dramatic photographs.

This season, the palm industry can expect similar treatment: activists will attempt to blame palm oil and plantation agriculture for both the fires and subsequent haze, just as they have done in the past. This is despite there being clear evidence that around 95 per cent of fires in Indonesia aren’t in oil palm plantations.