Earthworm Foundation, the quasi-NGO/for-profit business formerly known as The Forest Trust, released a new report arguing that overcapacity in palm oil mills in Kalimantan is driving forest loss.

Let’s be clear: Earthworm’s report aims to cut off investment in the palm oil supply chain, particularly in the rural areas of Central Kalimantan. This is a direct attack on jobs and small farmers.

Sadly, Earthworm has decided that an attack on Indonesia’s economy – during the middle of a pandemic – is the best policy prescription to the COVID crisis.

Earthworm’s report – a postgraduate paper from a student in Switzerland – urges local authorities to reduce mill license allocation because there is too much capacity already, and when there is underutilised capacity it will drive greater deforestation.

The political and technical points of the research are severely flawed. Many of which could have been ameliorated with double verification of claims, greater stakeholder consultation, including business operators, economists and traders, engagement with regulators and government officials and on-ground verification.

Flawed Arguments

The key argument put forward is that mill capacity is too high, and that is very much higher than the potential output of existing oil palm plantations. This results in supposed ‘hungry mills’, which are mills seeking greater supply of FFBs. It also argues that mills will be seeking to source from areas closer to their mills, which may prompt greater levels of deforestation around mills near forest areas. This is not a new idea; it has been advocated by an environmental program supported by the Climate and Land Use Alliance, UK Aid, and EU Commission, but nor does this theory put science first.

Mill Capacity

The first is that ‘capacity’ is theoretical. In a perfect world, mills – or any other industrial process – would run at 100 per cent capacity at all times. But the real world simply does not operate like this. Delivery and acceptance of FFBs varies according to any number of factors: e.g. rain can disrupt road transport, as can road closures. When FFBs are delivered, they become the responsibility of the mill; if there is loss and spoilage from that point onwards and subsequent lower quality oil, it is the mill’s responsibility. It is important that there is additional capacity to take higher and lower levels at different points in time. Similarly, CPO storage at the mill can limit throughput at particular points in time.

… Hungry Mills

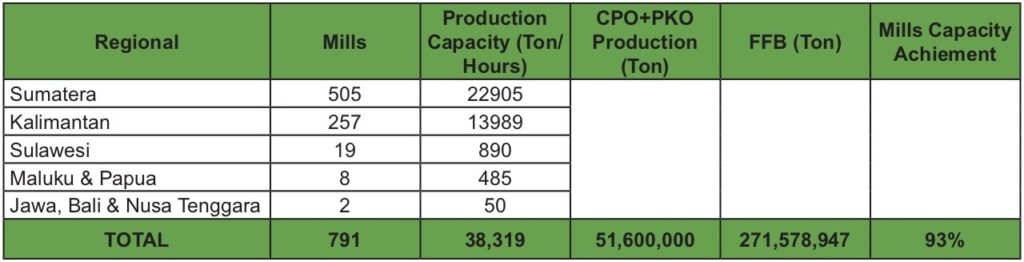

More to the point, Earthworm doesn’t want you to know that on-ground data from Indonesia, including evidence from financial institutions and research groups, indicates capacity utilisation across the country is about 93 per cent, which completely undermines the ‘hungry mills’ theory.

FFB Yield

The second is that because of the above, attempting to match FFB yield with capacity isn’t necessarily meaningful. The authors attempt to estimate yield for particular catchments based on the different types of production, e.g. independent smallholders, plasma, integrated. However, this isn’t always accurate. FFBs may be delivered, but they also may be rejected after grading at the mill. Yields are also dependent upon the reliability of the supply networks in the particular region. The large network of middlemen that operate between growers and mills does not appear to be accounted for in the study.

Small Farmers

The third is that additional capacity within a particular region is a positive for smallholder farmers. One of the key problems for smallholder farmers operating in many parts of Indonesia is that they are effectively faced with local monopolies. This means that they are price takers. Despite the publication of official regional FFB prices that should be paid at the mill, opportunism among local middlemen means that they pay for FFBs at a discount and sell to the mill at the official price. Additional mills and mill capacity for smallholder farmers in particular means that mills must actually compete with each other, increasing the bargaining power of small farmers.

Mill Catchment Areas

Finally, much of the study relies on the definition on mill catchment areas in terms of transport time between harvesting and processing. The baseline used is 24 hours, rather than the 48 hour industry standard. Although 48 hours is the maximum recommendation, the reality of this limit is quite different for smaller mills. The predicted catchment area – based on travel time – is wholly theoretical based on satellite data and estimates of the road network. Anyone familiar with Indonesia – particularly rural areas – knows that a ‘theoretical’ approach to road transport is difficult at best. Yes, caveats are provided, but this is precisely why only an interview/informant-based approach to the catchment areas is credible.

Impacts

- First, smallholders will likely suffer from reduced access and a level playing field. This will reduce prices, and reduce their incomes.

- Second, local communities will suffer if manufacturing and processing capacity is reduced, which will have flow-on effects for transport and logistics industries to job creation.

- Third, it will prevent the upgrading of existing mills using cleaner technology, including effluent capture.

- Fourth, it will undermine investment in rural areas. Central Kalimantan’s Human Development Index has been improving gradually over the past number of decades. This is because there has been considerable investment in the region; investment has created jobs, which has improved education outcomes and increased wealth.

- Fifth, it could undermine longer term economic goals for the province. Last year, the Widodo government announced that it would develop around 164,000ha of food estates, with much of the activity centred of Central Kalimantan. Is the Earthworm activity aimed at undermining the President’s development plans in rural Kalimantan?

- Finally, Earthworm will know that the longer it takes for the FFB to reach the mill, there can be public health consequences. Certain substances, such as 3-MCPD can be formed when the FFB takes too long to reach the mill. Is Earthworm knowingly recommending such a policy, given that it will harm smallholders, and potentially lead to suboptimal public health outcomes?

For Earthworm to spruik this paper as completed academic research is irresponsible. It appears to be an attempt by Earthworm to reduce the capacity of the existing industry in Central Kalimantan, and undermine the President’s agenda. Whatever the intention, Earthworm’s work is full of holes.